Do you remember the last time you went out and printed a snapshot? Or filled up a chunky, leather-bound photo album with a set of family portraits? With the immediacy of digital recording and the convenience of smartphones for organising and sharing images, the act of printing physical pictures has become something of an anachronism for anyone but hipsters and art photographers. And this is what i truley learnt from the lecture that Dr Francis took about Photographs being an object within an image. The generation nowadays dont really collect photos in physical albums eventhough that is one of the safest and oldest ways of storing photographs. Now you can have photographs in your phone or cloud albums however they cannot be touched with your hand, and they could easily be deleted or damged online.

INTRODUCTION: Photographs as objects. from PHOTOGRAPHS, OBEJECTS, HISTORIES, Elizabeth Edwards and Janice Elart, editors. Routledge, 2004

“The photograph was very old, the corners were blunted from having been pasted in an album, the sepia print had faded, and the picture just managed to show two children standing together at the end of a little wooden bridge in a glassed-in conservatory, what was called a Winter Garden in those days.“

In this introduction I can explain that the writer is aged, he is talking how a physical photograph is getting old and faded and that is because of how long ago it was taken, that photograph must of been decades old as he even says that the corners were blunted which shows that it was being flipped in the album book quite often. The central rationale of Photographs Objects Histories is that a photograph is a three- dimensional thing, not only a two-dimensional image. As such, photographs exist materially in the world, as chemical deposits on paper, as images mounted on a multitude of different sized, shaped, coloured and decorated cards, as subject to additions to their surface or as drawing their meanings from presentational forms such as frames and albums. Photographs are both images and physical objects that exist in time and space and thus in social and cultural experience.

KENNETH JOSEPHSON:

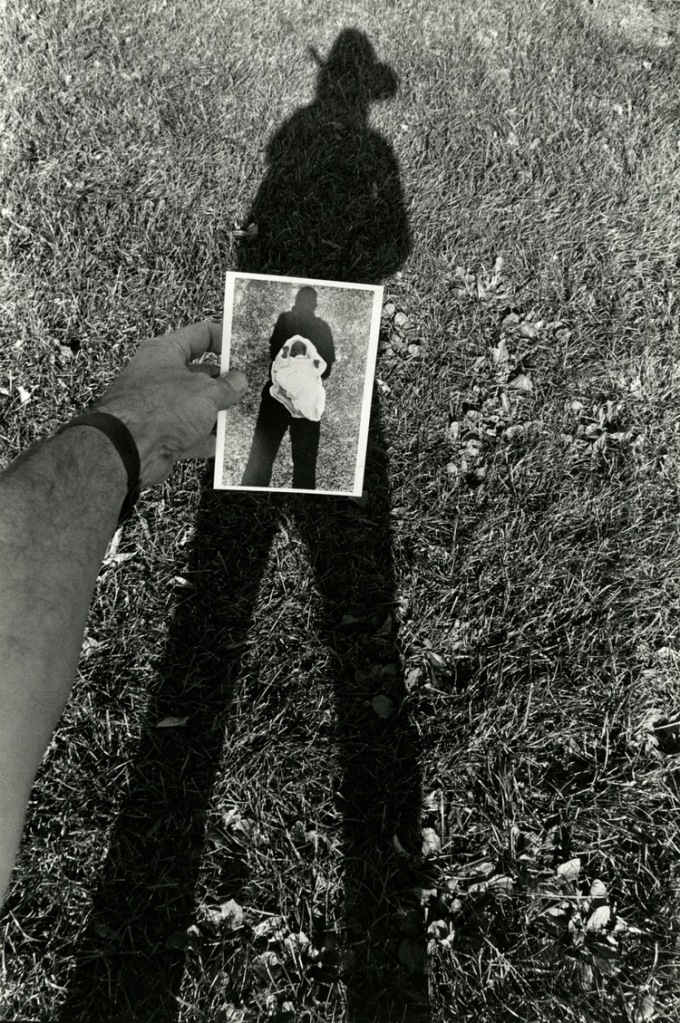

Kenneth Josephson is recognized as one of the pioneers of conceptual photography. He has explored the concepts of photographic truth and illusion throughout his career, producing a varied oeuvre that utilizes a range of techniques from collage and construction to multiple exposures and single negative photographs. Focusing on what it means to make a picture, Josephson’s work playfully highlights the illusive nature of photography.

His interest in the ways the camera manipulates what we see, how it abstracts space, compresses three dimensions into two, divorces subjects from their context and arrests time and motion—draws attention to the physical act of making a photograph and what that implies. Throughout his body of work, Josephson’s incisive commentary on the curiosities of photography as a descriptive medium and our belief in the image places his work at the vanguard of conceptual photography.

Maurizio Anzeri

Maurizio Anzeri makes his portraits by sewing directly into found vintage photographs. His embroidered patterns garnish the figures like elaborate costumes, but also suggest a psychological aura, as if revealing the person’s thoughts or feelings. The antique appearance of the photographs is often at odds with the sharp lines and silky shimmer of the threads. The combined media gives the effect of a dimension where history and future converge. The image used in Round Midnight is an early 20th century ‘glamour shot’ that at the time would have been considered titillating for both the girl’s nudity and ethnicity. Anzeri’s delicately stitched veil recasts the figure with an uncomfortable modesty, overlaying a past generation’s cross-cultural anxieties with an allusion to our own.

John Stezaker

John Stezaker’s work re-examines the various relationships to the photographic image: as documentation of truth, purveyor of memory, and symbol of modern culture. In his collages, Stezaker appropriates images found in books, magazines, and postcards and uses them as ‘readymades’. Through his elegant juxtapositions, Stezaker adopts the content and contexts of the original images to convey his own witty and poignant meanings.

In his Marriage series, Stezaker focuses on the concept of portraiture, both as art historical genre and public identity. Using publicity shots of classic film stars, Stezaker splices and overlaps famous faces, creating hybrid ‘icons’ that dissociate the familiar to create sensations of the uncanny. Coupling male and female identity into unified characters, Stezaker points to a disjointed harmony, where the irreconciliation of difference both complements and detracts from the whole. In his correlated images, personalities (and our idealisations of them) become ancillary and empty, rendered abject through their magnified flaws and struggle for visual dominance.

In using stylistic images from Hollywood’s golden era, Stezaker both temporally and conceptually engages with his interest in Surrealism. Placed in contemporary context, his portraits retain their aura of glamour, whilst simultaneously operating as exotic ‘artefacts’ of an obsolete culture. Similar to the photos of ‘primitivism’ published in George Bataille’s Documents, Stezaker’s portraits celebrate the grotesque, rendering the romance with modernism equally compelling and perverse.

Photography & Materiality: Window or object

In this particular lecture we learnt about how a photograph could be a picture or an ‘imprint’ ( iconic or indexical), We thought about how is a picture ‘constructed’- the snap-shot, the tableau or the montage.

We looked at the Western picture, the window through we are looking through. It is the depiction( or authoring) of a view/ the historical construction of seeing in a particulaer mode.

Dating back to the late sixties and early seventies, these rarely exhibited works chart Mapplethorpe’s experimental approach to subjects and mediums, demonstrating how the sensibilities shaped during this time would continue to inform his creative practice. These first gems of his artistic path undeniably present a sculptural quality and can be read like visual poems. For him, photography was a means to an end in a search for original self-expression. His utilitarian use of the medium resulted in a revolution for art photography. During Mapplethorpe’s lifetime, photography wasn’t a respected means of art making as it is today. He was able to bring photography into major museums during the course of his career, most notably one of his final shows at the Whitney Museum of American Art in 1989, and many museums posthumously.

Ken Jacibs, Windows, 1964

The picture as window can be understood more ‘photographically’ as the picture as de- limited frame. The moving camera shapes the screen image with great purposefulness, using the frame of a window as fulcrum upon which to wheel about the exterior scene. The zoom lens rips, pulling depth planes apart and slapping them together, contracting and expanding in concurrence with camera movements to impart a terrific apparent-motion to the complex of the object-forms pictured on the horizontal-vertical screen, its axis steadied by the audience’s sense of gravity. The camera’s movements in being transferred to objects tend also to be greatly magnified (instead of the camera the adjacent building turns).